Nine years ago, the Donetsk and Luhansk regions began to be associated among Europeans with war and devastation. A century and a half ago, Donbass had a completely different glory – it was a symbol of prosperity and wealth, many European countries willingly invested in it.

Factories, residential buildings, hospitals and shops rapidly expanded towns and cities during the “iron fever”, as that period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was called, by analogy with the “gold rush”. Donbass was built by the hands of desperate dreamers and prudent pragmatists who saw new opportunities for themselves on Ukrainian soil.

The history of Donbass is of great relevance to Europe as well. Some countries tried to forget about it – too traumatic memories, while others maintain the memory of those events to this day.

This story was reconstructed on the basis of the materials of the head of the department of scientific research of the history of Ukraine of the XIV – early XX century of the Dnipropetrovsk National Historical Museum named after Yavornytsky Valentina Lazebnik, interviews with her and with the historian, participant of the “DE NDE” initiative Leonid Marushchak.

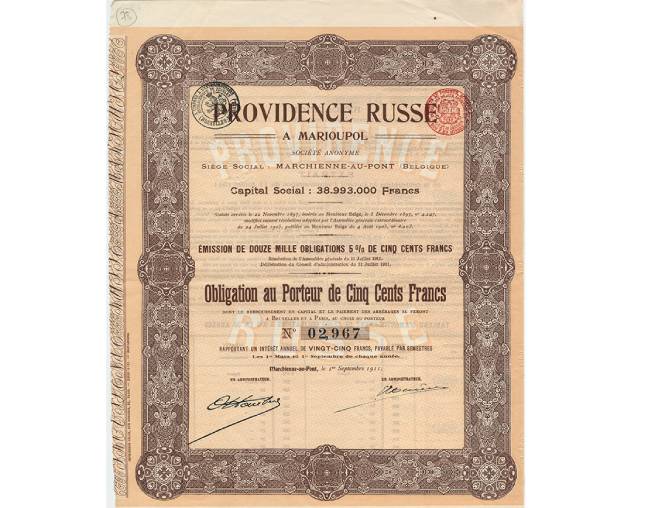

A few years ago, Valentina Lazebnik in Paris, among the antiques from one of the street vendors, saw a piece of paper with a familiar Ukrainian toponym. It was an action of one of the enterprises of Donbass. With over 100 years of history, it was now sold as a souvenir. Surprisingly, about 300,000 French residents still keep shares of Ukrainian enterprises left over from their ancestors who once invested in the development of Donbass. And if today Ukrainian papers have been preserved in such quantities by the French, it is difficult to imagine how many of them existed at the end of the 19th century, when they were worth their weight in gold.

Action “Russian Providence in Mariupol”. Dnipro resident Dmitry Pirkl was the first to massively collect shares of enterprises in the Donbass. He subsequently donated his collection to the museum. For historians, the collection of such shares, kept in the Dnepropetrovsk Historical Museum, has become one of the sources for studying the growth of the economy of the east of Ukraine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

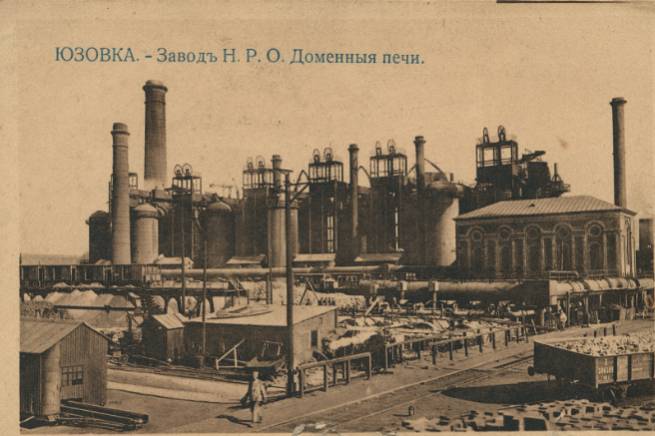

A well-known page in the formation of industry in the Donbass is associated with the name of John Hughes, a British entrepreneur. In 1869, he bought land on the banks of the Kalmius and began the construction of a metallurgical plant. So there was Yuzovka. Eight steamers transported equipment from the UK to the enterprise, and three years later the plant started working.

The name of John Hughes is well known to his contemporaries; at the beginning of the 21st century, a monument was erected to him in Donetsk. After him, the French also began to invest in the region, buying up mines and building a coal industry. Coal in the Donbass was of good quality, but iron ore was not of the highest quality. At first, ore for the Yuzovsky plant was transported from Kerch, then supplies were arranged from Krivoy Rog. Valentina Lazebnik says:

“I found a photo of how ore is transported from the mining site to Yekaterinoslav (now the city of Dnieper). In order to get further, to the Donbass, you need to cross the Dnieper. And the width of the Dnieper is a kilometer. How many oxen and wagons drowned in that Dnieper is unknown “Until the state built a railroad. And it was the first railroad that ran not from north to south, but from east to west: Krivoy Rog, through Yekaterinoslav – and to the Donbass. And it was specifically for the transportation of iron ore.”

The industry of eastern Ukraine developed slowly even before the construction of the railway branch. But when, instead of oxen, freight cars rushed across the steppes, this became a new stage for the development of the region. The first step to turn the Donbass steppes into “California’s gold mines” has been made.

Salt deposits in the Bakhmut region were known as early as the 18th century. In the second half of the 19th century, they began to develop deposits, but small enterprises had little capacity. In 1883, French bankers and entrepreneurs founded a salt mining company, which bought up salt mines near Bakhmut and created an industrial enterprise with rock salt mines and a salt factory. Soon it became one of the leaders in salt mining and the largest of its kind in Central and Eastern Europe. A significant part of the goods was exported.

In 1926, after the Bolsheviks nationalized the salt factories, the village was named after Karl Liebknecht. Subsequently, it grew into a city, and under independent Ukraine became Soledar, for which there have been fierce battles since August last year.

Valentina Lazebnik continues her story about the development of Donbass:

“After the construction of the railway in 1884, a new history of the region began. The British first came here, then the French, and then the Belgians en masse. Between 1895 and 1900, 20 factories were built at the expense of foreign investment. The factories grew like mushrooms after rain, five each year.”

At that time, European capital was actively looking for new territories for investment. It turned out that in the Donbass there is almost undeveloped land with many natural resources and the potential for cheap labor. Leonid Marushchak says:

“Russia needed new technologies and heavy industry, but did not have the resources for development. And then the empire decided to attract money from abroad. The state, represented by the Russian Empire, guaranteed its participation in what would contribute to these investment capitals. That no one would mislead investors. Special conditions were created to guarantee investment.”

The successful work of some factories inspired the opening of new ones. Enterprises of the metallurgical, iron ore, coal, manganese, chemical, and construction industries appeared. In 1892, the Donetsk soda plant (later Lisichansky) started operating. In 1983, they began to build the Druzhkovsky plant, and four years later – Toretsky, later they will be merged.

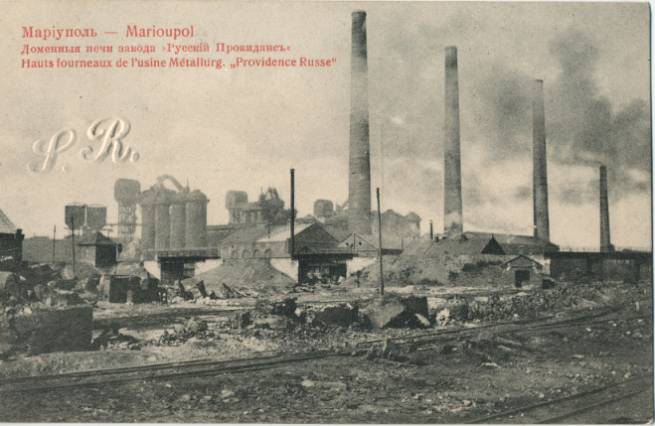

In 1896, the German entrepreneur Konrad Gamper founded a mechanical plant in Kramatorsk. His compatriot Gustav Hartmann built a locomotive plant in Lugansk. In 1887, in Mariupol, the pipe shop of the Nikopol-Mariupol Mining and Metallurgical Society produced its first products, and then the metallurgical plant “Providance” (Mariupol Ilyich Iron and Steel Works) began to work.

In the same year, the first smelting of cast iron was carried out at a metallurgical plant in Yenakiyevo. In 1899, the first blast furnace at the Makeevka plant was put into operation. Only in Konstantinovka for five years, from 1896 to 1900, Belgian entrepreneurs built glass, bottle, chemical, mirror and ceramic factories.

Heavy industry in the Donbass was built with the money of dozens of joint-stock companies. The metallurgical industry with 17 large factories was created entirely by Europeans – mainly Belgians, French and British. They also owned 24 coal mines. The region’s economy grew rapidly. The population also increased – people came in search of work and found it. Lazebnik says:

“Donbass became the world center of heavy industry, where the majority of high-class factories, mines and mines worked. If the coal industry worked at the expense of foreign capital, Franco-Belgian before, then metallurgy was approaching 100%. These were Franco-Belgian “, English and partly German capital. In Europe at that time, dividends on cash deposits in securities amounted to 3%. If five, this was already considered a very high percentage. But here they gave up to 40% profit.”

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, it was enough to add the name of one of the settlements or cities in the Donbass to the name of the joint-stock company – and the excitement around these shares on the stock exchange in Brussels was guaranteed. The dealers already knew that in this case it would be possible to make a big profit.

Infrastructure was built along with houses for workers. Schools and hospitals were opened, theaters, libraries were created, equestrian sports, football and tennis developed. Belgian industrialist Ernest Solvay arrived in Lisichansk only six years after his soda plant opened there – they finally built a hotel of the level that could accept it. Describing the Donbass of that time, Marushchak says:

“It was a goldmine, interaction with local and international capitals. A unique case of this kind. A win-win option.”

In the late 90s of the 18th century, a fire was lit in Mariupol. Huge shafts of smoke rose into the sky, and when there was a wind, dissipated over the city. Thus, specialists from Belgium studied the wind rose. They needed to understand in what direction the emissions would go when heavy metallurgical production began to work.

Machines, equipment and even building materials for the Nikopol plant in Mariupol were transported by steamboats from the USA to the Crimea. And from there – by rail to the city of Mary. Several dozen specialists who launched production were also from America. Nikopol produced armor for ships, cast iron and pipes. Later, the Americans will sell their stake in the enterprise to investors from Belgium and France.

Another metallurgical plant “Providence” was built nearby. Its products are cast iron, steel, railway rails and cast iron. In 1919, these factories were merged, and in 1924 they were named after Lenin.

Before the start of the World War, there were consulates of eight European states in Mariupol. It had its own customs and exchange. The city was called a window to Europe. How did the collapse of the Donbass dream happen? A significant role in this was played by the workers of factories with foreign capital, who, from their own experience, could feel the difference between their profits and the wages of foreign specialists. When the revolutionary movement began in Russia, part of the workers actively supported it.

The October Revolution of 1917 announced a course towards the liquidation of capitalism. Nationalization has begun. Foreigners massively began to leave Donbass. In 1918, the Council of People’s Commissars issued a decree nationalizing enterprises in a number of industries and transport sectors with a fixed capital of a million rubles or more. Technical staff and managers were forbidden to leave work at enterprises under pain of a revolutionary tribunal. However, all the same, foreign engineers, highly skilled craftsmen found ways to return home.

Securities were also nationalized – locals were ordered to hand over to banks. The person who kept the shares could be punished up to and including execution. Leonid Marushchak says:

“The French hate to think about it. For them it is a tragic topic on a national scale, even though this is the beginning of the 20th century. Many families lost capital, lost the business that was here. Not only did they not make a profit, they were deprived of the opportunity take away part of the property.

After the Bolsheviks began to lead the industry, and the European specialists fled, some of the enterprises simply stood up. To resume production, personnel were needed. And the Europeans, who unsuccessfully tried to return at least some property through the European courts, considered it pointless to go to Donbass again. The Soviets turned to the Americans for help:

“In the 1920s and 1930s, foreigners were invited to build an industrial Donbass. There were no specialists, professors and engineers were destroyed during the repressions, so international companies were invited.”

The plant in Kramatorsk, for example, stopped in 1921 due to a shortage of specialists. The situation was corrected by the involvement of a team of 20 American engineers who returned the enterprise to full-fledged work. However, later they were refused to be paid in foreign currency, and they left. Then about 500 Germans were invited to Ukraine, who agreed to receive a salary in rubles. Labeznik says:

“The myth of the Soviet technological breakthrough that Stalin spoke about would not have existed without Germany and the United States. Without them, the factories that were lost during the civil war would not have been restored.”

The topic of industrialization of Donbass has long been under an unspoken ban on research. Documentary evidence was taken out. Finding information in museums was difficult. However, the buildings designed by European architects remained, preserved the history and unusual names for Ukraine on the tombstones of cemeteries. The conversation that Leonid Marushchak recalls is indicative. Once he spoke with one of the workers who worked for 30 years at a factory in eastern Ukraine. And he talked about the equipment with the stamps of European cities and the date of 1889, which he saw every day. But the man did not even suspect the real reason for how such equipment appeared here. For years, the man explained to himself incomprehensible stamps by the fact that the equipment seemed to have been brought from an evacuated European enterprise during the Second World War. “These are myths that people were satisfied with, and everything was fine,” says Maruschak. “People believed.”

More Stories

Making a mockery of the Acropolis for the sake of tourism

How Plato spent his last night – what the found papyri showed

Eurovision 2024: the first rehearsal of Marina Satti in Malmö has ended