The legendary star catalog compiled by the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus was considered lost, but scientists found it in a medieval manuscript, on parchment, from which the Greek text was scraped.

A medieval parchment from a monastery in Egypt turned out to be an amazing treasure. Beneath the Christian texts, scientists have discovered what appears to be part of the long-lost astronomer Hipparchus’ star catalogue, believed to be the earliest known attempt to map the sky.

Scholars have been searching for Hipparchus’ catalog for centuries. James Evans, an astronomy historian at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, describes the find as “rare” and “incredible.” An excerpt posted online this week at Journal for the History of Astronomy one . Evans says this proves that Hipparchus, often regarded as ancient Greece’s greatest astronomer, actually mapped the sky centuries before other known attempts. It also illuminates a defining moment in the birth of science, when astronomers moved from simply describing the patterns they saw in the sky to measuring and predicting them.

The manuscript came from a Greek Orthodox monastery Saint Catherine in the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, but most of the 146 folios, or manuscripts, now belong to the Museum of the Bible in Washington (CC BY SA 4.0). The pages contain the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a collection of Syriac texts written in the tenth or eleventh centuries. But this codex is a palimpsest: parchment from which the scribe scraped off the old text so that it could be reused.

The older writings were thought to contain further Christian texts, and in 2012 biblical scholar Peter Williams of the University of Cambridge (UK) asked his students to study these pages as a summer project. One of them, Jamie Clare, suddenly noticed a passage in Greek that is often attributed to the astronomer Eratosthenes. In 2017, the pages were re-analyzed using state-of-the-art multispectral imaging. Researchers at the Electronic Library of Early Manuscripts in Rolling Hills Estates, California, and the University of Rochester in New York took 42 photographs of each page in various wavelengths of light and used computer algorithms to find combinations of frequencies that enhanced the hidden text.

star signs

Nine folios contain astronomical material which (according to radiocarbon dating and writing style) was probably copied in the fifth or sixth century. It includes the myths about the origin of the stars of Eratosthenes and part of the famous poem of the third century BC called Phaenomena, which describes the constellations. Then, while viewing images during the coronavirus lockdown, Williams noticed something much more unusual. He reported this to the historian Victor Gizemberg of the French national research center CNRS in Paris. “I was very excited from the very beginning,” says Gizemberg, “it was immediately clear that we had the coordinates of the star.”

A sequence of spectral images obtained by the Digital Library of Early Manuscripts and the Lazarus Project.

This crossfade montage shows the detail of the palimpsest in normal light, multispectral analysis, and hidden text reconstruction.Credit: Museum of the Bible (CC BY-SA 4.0). Photo: Early Manuscript Library/Lazarus Project, University of Rochester; multispectral processing – Keith T. Knox; drawing – Emanuel Zingg.

The surviving passage, transcribed by Giesemberg and his colleague Emmanuel Zing at the Sorbonne University in Paris, takes up about a page. It shows the length and width in degrees of the constellation Corona Borealis, the northern corona, and gives the coordinates of the stars in the extreme north, south, east and west.

Several pieces of evidence point to Hipparchus as the source, starting with the idiosyncratic way in which some of the data is expressed. And, crucially, the accuracy of the ancient astronomer’s measurements allowed the team to date the observations. The phenomenon of precession – when the Earth slowly rotates on its axis by about one degree every 72 years – means that the position of the “fixed” stars is slowly shifting in the sky. The researchers were able to use this phenomenon to check when the ancient astronomer should have made his observations, and found that the coordinates corresponded to approximately 129 BC, the time Hipparchus was working.

Until now, Evans says, the only star catalog surviving from antiquity was that compiled by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy in Alexandria, Egypt, in the second century AD. His treatise Almagest, one of the most influential scientific texts in history, outlined a mathematical model of the cosmos – with the Earth at its center – that has been accepted for over 1,200 years. He also gave the coordinates and magnitudes of over 1,000 stars. However, in ancient sources it is repeatedly mentioned that the person who first measured the stars was Hipparchus, who worked on the Greek island of Rhodes three centuries earlier, between about 190 and 120 BC.

Location of the stars

Babylonian astronomers had previously measured the position of certain stars around the zodiac – constellations located along the ecliptic – the annual path of the Sun relative to fixed stars, as seen from Earth. But Hipparchus was the first to determine the location of the stars using two coordinates and made a map of the stars in the entire sky. Among other things, it was Hipparchus who first discovered the precession of the Earth and modeled the apparent movements of the Sun and Moon.

Gizemberg and colleagues used their findings to confirm that the coordinates of three other star constellations (Ursus Major, Ursus Minor, and Draco) in a separate medieval Latin manuscript known as Aratus Latinus must also have been derived directly from Hipparchus. “The new snippet makes it much, much clearer,” says Mathieu Ossendrijver, an astronomy historian at the Free University of Berlin. “This stellar catalog, which had been floating around in literature like an almost hypothetical thing, became very concrete.”

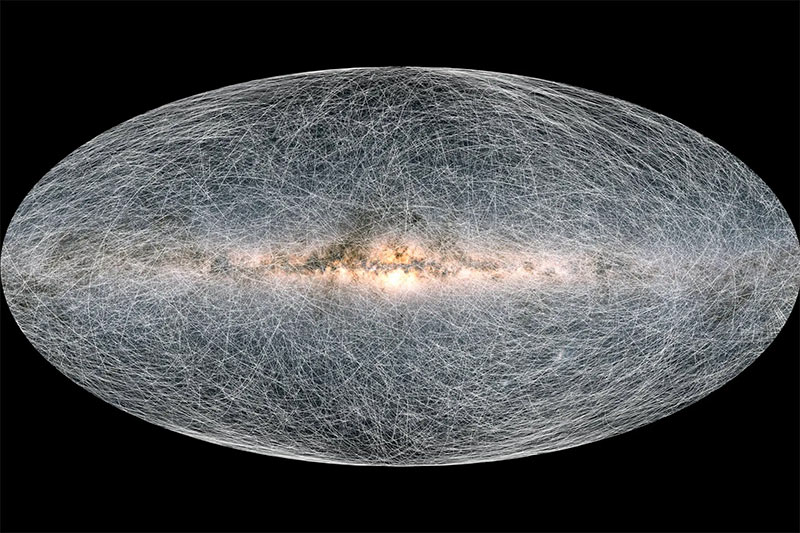

The best map of the Milky Way shows a billion stars in motion

Researchers believe that Hipparchus’ original list, like Ptolemy’s, must have included sightings of almost every visible star in the sky. Lacking a telescope, Giesemberg says, he had to use a spotting scope known as a diopter, or a mechanism called an armillary sphere. “That’s countless hours of work.”

Relations between Hipparchus and Ptolemy have always been murky. Some scholars suggest that Hipparchus’ catalog never existed. Others (beginning with the 16th-century astronomer Tycho Brahe) have argued that Ptolemy stole Hipparchus’ data and appropriated it for himself. “Many people think that Hipparchus was a really great discoverer,” says Gizemberg, while Ptolemy was “an amazing teacher” who pieced together the work of his predecessors.

Based on the data contained in the fragments, the team concluded that Ptolemy did not simply copy Hipparchus’ figures. But perhaps he should have done so: Hipparchus’ observations seem to be much more accurate: the coordinates read so far are correct to within one degree. And if Ptolemy based his coordinate system on the ecliptic, then Hipparchus used the celestial equator – a system more common in modern star maps.

The birth of the field

The discovery “enriches our understanding” of Hipparchus, Evans says. “It gives us a fascinating glimpse into what he actually did.” And in doing so, it sheds light on a pivotal event in Western civilization, the “mathematization of nature,” when scientists seeking to understand the universe moved from simply describing the patterns they saw to trying to measure, calculate, and predict.

Hipparchus was the key figure responsible for “turning astronomy into a predictive science,” agrees Ossendrijver. In his only surviving work, Hipparchus criticized earlier authors of astronomical writings for not caring about numerical precision in their ideas about orbits and celestial spheres.

He is thought to have been inspired by contact with Babylonian astronomers who had access to centuries of accurate observations. The Babylonians were not interested in modeling the three-dimensional structure of the solar system, but due to their belief in celestial omens, they made accurate observations and developed mathematical methods to model and predict the timing of events such as lunar eclipses. With the advent of Hipparchus, this tradition combined with the Greek geometrical approach, says Evans, and “modern astronomy began.”

The researchers hope that as imaging techniques improve, they will be able to discover new stellar coordinates, allowing them to have a larger dataset to study. Some parts of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus have not yet been deciphered. It is also possible that additional pages of the star catalog are preserved in St. Catherine’s Library, which contains over 160 palimpsests. As a result of attempts to read them, previously unknown Greek medical texts have already been discovered, including prescriptions for medicines, surgical instructions and a guide to medicinal plants.

In addition, multispectral visualization of palimpsests reveals new rich layers of ancient texts in archives around the world. “In Europe alone, there are literally thousands of palimpsests in major libraries,” says Gizemberg. “That’s just one case, very exciting, the possibility of researching which can be applied to thousands of manuscripts with amazing discoveries each time.”

source: nature.com

More Stories

Making a mockery of the Acropolis for the sake of tourism

How Plato spent his last night – what the found papyri showed

Eurovision 2024: the first rehearsal of Marina Satti in Malmö has ended