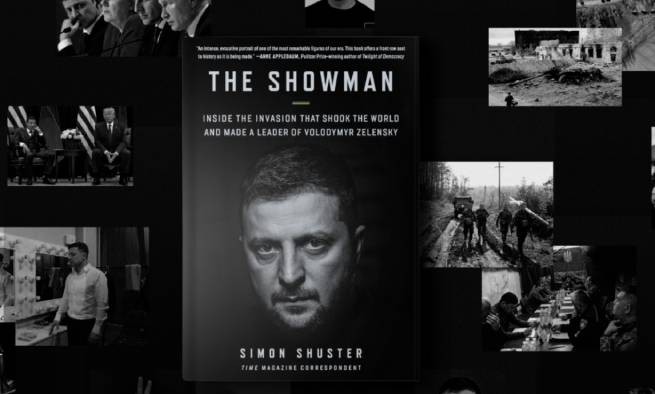

Simon Schuster, a Time journalist, spent most of the first year of the war with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. About everything he saw and his own assessment – in the book “Showman” published in English, which caused a mixed reaction in the world.

“I do not know whether he will have the wisdom and restraint to give up the extraordinary power he received in wartime, or whether he will become too dependent on it,” the author’s summary says.

Pulitzer Prize winner and author of the book “Red Famine: Stalin’s War against Ukraine” Anne Applebaum wrote this about the book of her American colleague Simon Schuster, which is published by the English-language publishing company Harper Collins*, one of the “big five” largest publishing houses in the world:

“A powerful portrait of one of the most towering figures of our era, this book offers a front-row seat to history as it was made.”

Times correspondent Shuster had unprecedented access to the Ukrainian president and his team in the first year of the full-scale Russian invasion. In Ukraine, many are skeptical about the journalist, who was born in Moscow, and after emigrating to the United States, he returned to the Russian capital from there to write for international news agencies. Therefore, many of Shuster’s materials about the full-scale invasion in the Times magazine were also perceived in Ukraine with a certain skepticism.

But The Showman has already been recognized abroad; in Britain, for example, it became the book of the month in the Independent and in the largest bookstore chain Waterstone, and the Guardian wrote that this book is a must-read in 2024. Why is there so much talk about her? Tells Forbes, introducing Time journalist Simon Schuster to the book.

It has everything: how Zelensky agreed with Western allies on the transfer of weapons, about the life of the president’s team in a bunker, about the trip to liberated Kherson and the “No Mercy” order.

Until the last hours, President of Ukraine Vladimir Zelensky did not believe that a big war would start. On the evening of February 23, his wife Elena Zelenskaya planned to pack her suitcase, but did not have time – she and the children were doing school homework, having dinner, and watching TV. Around four in the morning, Zelenskaya woke up from the explosions and went into the next room. Her husband stood there, dressed in a suit: “It has begun.”

In the book “Showman: Inside the Invasion that Shocked the World and Made Vladimir Zelensky a Leader,” Simon Schuster describes the events of the first day of the big war. This is a military biography of Zelensky. She describes the process of transforming a showman into a wartime leader of a state. At the same time, as the author says, “40% of the book is devoted to his life before politics, Krivoy Rog, KVN, and 60% to the presidency with an emphasis on 2022.” Shuster recalls what the president knew about his work on the book:

“He said that he was not against it, but isn’t it too early, because the matter is not completed yet. He repeated this thought more than once.”

The first scandal has already been noted on the account of “Showman”. On January 10, journalist Nina Kuryata published a post about the book and suggested that Shuster was in Zelensky’s bunker. In comments, Advisor to the Head of the Presidential Office Sergei Leshchenko said: claiming that he was there for at least a minute, Shuster is lying, to which the journalist replied:

“Descriptions of life in the bunker are based on interviews with the president and people who lived and worked there.”

Shuster says that in early April, the president’s team was already working more often in their usual offices:

“It helped me because I could come to them. No one was allowed into the room where they had been before, especially a foreign citizen.”

Reviews of Simon Schuster’s book are mixed. But in order to have your own opinion, you should familiarize yourself with it. Forbes and other media give a brief summary of what it’s about.

“The war is not over yet, not even close. But the man at the center has already become a wartime leader.”, says an excerpt from The Showman on The Telegraph website. Shuster came to this conclusion when he saw Zelensky on his way to the Capitol during a visit to Washington in December 2022. It reminded him of “a bulldog on his way to a fight.”

Shuster began observing Zelensky closely during the war in April 2022. Then he spent a lot of time on Bankova. Sometimes, despite the sirens, everything seemed almost normal, the journalist recalls:

“We joked and drank coffee, but it was a time of exhaustion and fear.”

The days of the Ukrainian president then consisted of interviews, meetings, conferences, and reception of foreign leaders and diplomats. In “Showman”, where the events end at the end of 2022, a series of key events of that year are described: February 24, the battles for Gostomel airport, the months spent in the bunker, the visit of the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, Zelensky’s trip to liberated Kherson and others . The author retells each episode in his book from the words of the president and his entourage. Describing life in the bunker, he quotes a minister who recalls that for several days he ate nothing but chocolate:

“There wasn’t much food. Sweets were distributed at meetings, and there was canned meat and dry bread in the kitchen.”

Zelensky complained about the lack of air and sun. A spokeswoman for his team compared the president to a “living corpse.” Little by little the situation improved. Zelensky began to start the day with breakfast; sports equipment and a ping-pong table appeared in the bunker.

At the beginning of the invasion, European leaders offered Zelensky assistance in escaping the country. He took this as an insult. The president turned every conversation towards providing weapons to Ukraine and became irritated when he was asked to leave. “It tired me,” he said.

Shuster praises Zelensky’s success in arms agreements, demonstrating this particularly well in one episode: “At first, Biden did not want to send systems like HIMARS. Every decision regarding the supply of weapons was not easy.” He recalls a telephone conversation between the presidents in June, when the United States agreed on the transfer of HIMARS and approved a $1 billion aid project:

“Zelensky thanked him and immediately began reading out the list of weapons Ukraine needs. According to people involved in the conversation, Biden took some offense. But such diplomacy turned out to be effective.”

A rare case, writes Schuster, when Zelensky’s skill as an orator failed him was a meeting with Ursula von der Leyen on April 8 in Kyiv. That morning, Russia launched a missile attack on the Kramatorsk train station. More than 60 people died. The attack shocked Zelensky, he could not focus. Zelensky told Shuster:

“The arms and legs are doing one thing, but the head is not listening. Because the head is at that station.”

“Another trait of Vladimir Zelensky that caught my eye is his ignoring of danger signals,” says Shuster. The book describes at least three situations when Vladimir Zelensky put not only himself, but also other people at risk of death: when before his concert a message was received about the bombing of the concert hall, when on the front line he was in the range of Russian snipers’ fire, and, well, , of course, when, having received many messages about Putin’s planned invasion, he said until the very end that this was panic-mongering, promised “kebabs” and did not even prepare his children and wife for this.

In the fall of 2022, Zelensky’s team went to liberated Kherson. Shuster received a message from the President’s Office: get ready for a trip. It was important for the president to show that Ukraine has returned and will help its citizens, he says. The stakes were high: during the visit, a Russian UAV was flying over the main square of the city. “When we discussed this with the president, he admitted that it was frivolous,” Shuster says. “The security advised us to wait a few days until sappers and the SBU walked through the city.”

The fundamental theme of “Showman” is Zelensky’s transformation. Shuster says:

“I was able to communicate with people in the process of its evolution, at different stages of governing the country during the invasion. I was able to follow how he changes, his approaches and character.”

The author notes how quickly the president masters various areas – from the economy to war. At the beginning of the invasion, Zelensky let the military fight and did not interfere. Subsequently, interlocutors began to tell Shuster that the president plays an active role in making important decisions. “This is the evolution of his understanding of military affairs,” the journalist notes.

The journalist believes that Zelensky underwent the biggest changes in the first months of the invasion: “Stubborn, vindictive, apolitical, bold to the point of recklessness, he directed anger and resilience at his people and expressed them to the world.” In the section on the battle for Gostomel airport, he describes how the enraged president gave orders: “No mercy – use all weapons and destroy everything Russian there.”

When Shuster asked the president himself about the changes, he replied that he had grown very old and would no longer be the person he was before the war. “Several of his advisers told me that he doesn’t smile or joke,” the journalist says. “He still has a sense of humor, but he has become tougher in his communication.”

Shuster studied what skills as an artist and producer helped Zelensky fight the war. The showmanship that he honed for more than 20 years made him effective, the author is sure. Flexibility in thinking and approach was helpful. “In his previous life, he had to adapt to new unexpected challenges, roles, improvisations. This saved me when I had to transform from president to military commander within 24 hours,” says Shuster.

Another habit of Zelensky since the days of KVN is respect for collective thinking, notes Shuster:

“He often started our conversations with the question: what do you think about this? What about the Americans? Members of OP’s large team who are responsible for the website or photo service told me the same thing – at meetings he addresses them as well.”

Shuster also expresses concern about the changes he noticed in Zelensky. In The Showman, the author reflects on what will happen after the war: “I don’t know whether he will have the wisdom and restraint to give up the extraordinary power he received in wartime, or whether he will become too dependent on it.”

Simon Shuster probably had the greatest access to Vladimir Zelensky among all Ukrainian and foreign journalists: from his first concert after his presidential nomination to his election as head of state and the onset of a full-scale war, he repeatedly accompanied him on trips (including to the front), traveled with him on trains, planes and even had dinner (at least once).

Since 2019, he has observed his character in very different situations, and the psychological portrait of Vladimir Zelensky looks like this: he is a very stubborn person, very sensitive to any criticism and sometimes very naive. This concerns not only his journey from show business to politics, but also his hopes to somehow persuade or outplay Vladimir Putin.

*HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the largest publishing companies in the world, one of the “Big Five” English-language publishers along with Hachette, Holtzbrinck/Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster. The company’s headquarters are located in New York. It is a subsidiary of News Corp.

More Stories

What influenced Greece’s decision to help Kyiv with weapons?

The Minister of Health called the protesters "insignificant people, kafirs"

Gold Switzerland: “We are in the last 5 minutes of our financial system – the collapse of everything is approaching”