The myth of Inoia, who was turned into a crane by the goddess Ira, turned into a story “about storks delivering babies to their parents.”

When she was five, says Isabelle Gertsen, a BBC writer, she received an unexpected gift from her grandmother: a picture book detailing how a man and a woman “make a baby.” She and her sister were excited. “Until then, our only guide to where babies come from was Disney’s Dumbo delivered to his mother by a stork. Our mother, having caught us studying the book, was embarrassed and put the publication on a high shelf, hoping that this would be the end of it all. But we just climbed onto a chair and continued an interesting activity, laughing and bashfully looking at the anatomy of the body. After that, a flurry of questions fell upon our parents, which they did their best to avoid.

Isabelle Gertsen’s parents did have the infamous “conversation” with their children a few years later when they felt they were old enough to learn the truth about sex, childbirth, and puberty. Sex education was also part of the curriculum in the Dutch and English elementary schools they attended. However, many children around the world are not properly taught about sex until they are in high school, if at all.

“There are definitely still a lot of kids who get their answers to where babies come from from folk tales or mythology,” Lucy Emmerson, executive director of the UK Sex Education Forum, told the BBC. Can such myths and euphemisms – be they classic fairy tales about children delivered by storks or found in cabbage fields, or are more recent spontaneous inventions really going to change how we think about sex in the long run? And how did they appear?

A closer look at some of the oldest myths about sex and children reveals exciting insights into why people tell them and how we could do better.

In Scotland, children put cabbage leaves outside their homes to ask the fairies to bring them a new brother or sister. Most children are faced with a story about a stork. Disney movies, cartoons and picture books show how these elegant long-legged birds deliver newborns to their parents.

The “dark” myth of Inoia

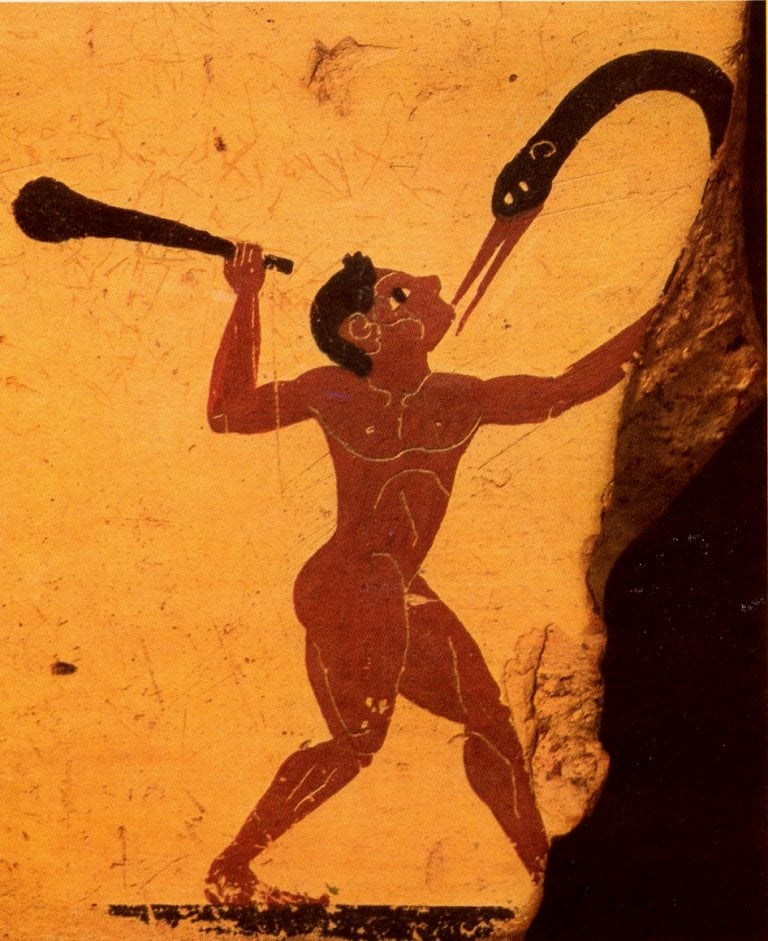

The original myth has a darker twist: a bird steals—or saves, depending on your point of view—a child. The myth goes back to the origins of Ancient Greece, where cranes, which have much in common with storks, were associated with stealing babies. This is definitely the story of Inoja.

Inoye belonged to a tribe of pygmies. She was very beautiful, but with a bad temper, she even despised Artemis and Hera, while there were suspicions that she had a connection with Zeus. The goddess of the family punished her for her arrogance by depriving her of the opportunity to be with her child.

When Mopsos was born, the fruit of the marriage of Inoye with the sensible Nicodamanthas, the pygmies offered the newborn many gifts. Hera then turned her mother into a crane, a high-flying bird with a long neck, and caused discord between her and the pygmies. This war never stopped because Inoye, not wanting to leave her child, carried him with her in her beak, in a makeshift cradle (in a blanket). Armed pygmies chased after her.

With time the crane has become associated with the stork, Paul Quinn, senior lecturer in English literature at the University of Chichester in the UK, tells the BBC: “There is a connection to domestic life because storks nest on people’s rooftops.” Another a mythological layer added a pelican, which in European medieval literature was symbol of the Virgin Mary and nursing mothersays Quinn. He explains that the pelican has also been associated with breastfeedingbecause in the literature this bird is described as “having a massive chest (crop) to feed its chicks.”

Storks of the storyteller Hans Christian Andersen

At the beginning of the 19th century, the stork began to appear in fairy tales. Again, he tended to appear as symbol of home life and family. “Storks have always been associated with family life because they have been seen nursing their young,” Marina Warner, professor of English and writing at Birkbeck College, University of London, told the BBC. In fairy tales, they often come to save human babies, i.e. “the stork finds babies in wells, lakes or swamps and uses its beak to pull them out.” This version was popularized by Hans Christian Andersen’s short story “The Storks”, published in the early 19th century.

In Andersen’s tale, the white birds are looking for “the pond where all the little children are waiting for the storks to come and take them to their parents.” “The most beautiful babies lie there and cherish their sweet dreams,” writes Andersen. “All parents are happy to have a small child, and children are so happy if they have a little brother or sister.”

But in history Andersen has a cruel twist: delinquent children are punished by the stork’s dead brother to mourn their “little dead brother”. Despite the horrific ending, Andersen’s story quickly swept the English-speaking world.

In Victorian Britain, the stork became a convenient way for confused parents to explain the facts of life to their children and hide the realities of sex and childbirth.

In its most innocent form the myth of storks is still present in popular culture. To this day the usual a birthmark on the skin of a newborn, caused by malformations of the blood vessels, is still called the “stork sting”.

From stories to reality

The school is in no hurry to correct such gaps and misunderstandings. In the US, only 29 out of 50 states have officially introduced sex education in schools. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, less than half of high schools and less than one-fifth of high schools teach basic sex education topics. AT UK children are taught about relationships in primary school, but primary schools are not required to teach sex educationwhich become mandatory only in high school.

Even where the corresponding the lesson exists, it is not always taught correctly. An example is the video “συναίνεση, είναι απλό σαν τσάι”, produced by the Thames Valley Police and widely shown in schools. Video compares the mood for sex to offering to make someone a cup of tea and reminds young people that wanting a cup of tea (or sex) one day doesn’t automatically mean they want it another day. And that’s where the information ends.

So if a parent was thinking “if I don’t say anything, they’ll know when they get to school”, it probably isn’t. Parents can start with short, simple conversations instead of long discussions. It starts as early as kindergarten, when children are taught basic information about their bodies as well as their emotions. For example, if a small child asks how children are born, it is enough to say that the child grows in the mother’s belly and comes out of the vagina. This is not about explaining the sexual act. But this is a real, not a made-up answer.

Vital concepts such as consent and protecting personal boundaries can also be taught early on. Does this mean that charming stories about storks and cabbages have no place in today’s parenting culture? There are, as long as they are treated like fairy tales.

More Stories

Schools in Germany: convert to Islam so as not to be an outsider

On this day in 1896, a statue was found in Delphi "Delphic Charioteer"

Notre Dame is promised to be renovated for the Olympics in Paris