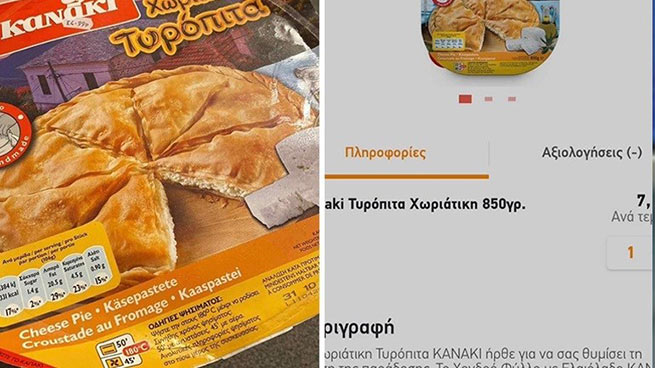

In a British supermarket, where the average resident earns about three times the salary of the corresponding Greek worker, the tiropita (cheese pie) made in Greece by Kanakis sells for 30% less than in Greece.

Oxymoron – incomprehensible, absurd, but at the same time disturbing. How can a product made in Greece and delivered to England, which is outside EU, and therefore this food product is subject to duty, cost less on the English shelf than on the Greek one? The price difference is significant. This particular product, frozen tyropita, in an English supermarket where it was spotted by a reader of a Greek edition”Zougla“, costs 5.72 euros (£4.99), while in Greece the exact same package costs 7.12 euros.

Economists will argue that the UK is a country with tens of millions of consumers, while the Greek market is extremely limited. That is, a product that is massively imported into Britain has a lower purchase price from the manufacturer due to the large quantity on order. This argument suggests that the Greek cheese pies company is capable of supplying such high volumes. It is the situation with prices that is explained by economic experts who advise the Greek government.

Zougla journalists turned to the consumer service of Hellenic Quality Foods or HQF – “Kanakis”, one of the largest food companies in Greece, to answer the main question that torments us:Why does the Kanakis village cheese pie sell for €5.72 (£4.99) in a London supermarket and €7.12 in Greece?

Answer:

“Obviously the chains are doing promotions, the final price depends on the retailer. We make various agreements, and it goes without saying that each chain will set its own price limit, up to the ceiling set by the ministry. Now abroad if you go to another chain, you will find it at a different price.. This particular chain, which I don’t know, wanted to do a (promotion) to sell a few pieces – ok, we are aware, we have an export department – they have the right to do so. In any case, we are not talking about a huge difference, that is, it was a little more expensive than 1 euro,” they answered us, clearly annoyed.

We then pointed out that the price reasonably includes the cost of transportation to a foreign country, customs duties and, among other things, the UK is outside the European Union, so why is London cheap?

Answer:

“No, it’s not. The same product in Australia where we have customers sells for the same price. It’s a matter of the actions they take on other products you see (price difference) but not necessarily regarding food.In England you can find this product at a different price than in Greece.The difference mentioned by the buyer (a consumer who contacted them about the same issue) is 1.50 euros.I think that each chain with its own potential to carry out such an action.

And concludes: “To put it simply, and I don’t know how it’s going to sound, maybe there are a few pieces left and she wants to sell them because she doesn’t want them to expire. I don’t know the story, so I was looking for information.”

We note that the company’s reasoning betrays embarrassment and probably an inability to rationally explain the irrational event. The commercial policy of the company depends on random circumstances and seasonal moods not even of the wholesale British importer, but of the final retailer. Indeed, in the company’s closing argument we heard, it refers to various hypothetical scenarios that could potentially be developed by officials in retail chains south of Leicestershire or in the suburbs of Newcastle.

But that doesn’t explain how a frozen cheese pie ends up costing the Greek consumer €7.12. I wonder what’s to blame for this? The price of a kilogram of feta? Rising prices for spinach and greens? None of the above, obviously. The final price of a product in a Greek supermarket is determined by the appetites, needs or intentions of intermediary merchants and the complete lack of control by the competent ministry. In a word, the irrational formation of the final price due to the uncontrolled rate of return at various stages of the distribution of the product.

However, the answers to this question should not be given by us, but by the minister himself, Mr. Adonis Georgiades. At the time of writing, a liter of private label sunflower oil in a large supermarket chain in Greece is selling for more than twice as much as it did a month ago. The current price is almost the same as the prices of competing companies.

Conclusions: what kind of family basket are we talking about, and what kind of price containment are we striving for?!

Under such conditions and with the right attitude, Greece is understandably the kingdom of obscenity barons. A well-known viral response from a sympathetic fellow citizen to a morning show reporter about the “home basket,” the core of government propaganda, confirms the prevailing view. Talk of price moderation and the householder’s basket is the traditional blah blah blah. Can this now historic phrase become a major election slogan, comparable to those that at times constituted the majority of ideological currents in post-independence Greece.

More Stories

Flood victims in Thessaly will pay property tax (ENFIA)

Fines of 1.5 million euros for 11 large retail chains, including Leroy Merlin, Attica and JYSK

MyCoast: A digital app for complaining about beaches