Until the late 1980s, advertisements for private detectives advertised their services along with “divorce, surveillance, premarital affairs” as well as “τηλεμαγνητοφωνήσεις”.

It was common knowledge that this vague term included (illegal) interception of telephone calls. This was usually done by connecting a tape recorder or radio transmitter to the point where the victim’s telephone cable terminated, in a so-called “cafao”. These gray boxes, seen on the sidewalks in every neighborhood, collect telephone lines from several streets to connect them to the building that houses the entire neighborhood’s telephone exchange. Usually they are called main junction boxes – the word “kafao” comes from the Greek pronunciation of the letters KV of the corresponding German term Kabelverzweiger. Being unguarded and easily hacked, they were the perfect place for detectives and, I suspect, government agencies to install telephone surveillance devices.

In the mid-1990s, the way telephone conversations were monitored began to change due to two opposing forces brought about by technological advances. On the one hand, the digitalization of the network (and later the advent of mobile phones) has made it more difficult to install monitoring devices in call centers and external exchanges. It’s a problem similar to the one we faced when the transition to digital television forced us to add set-top boxes to all our old TVs in 2015. On the other hand, digital call centers have made it much easier to monitor calls from a central location. Monitoring is a call center feature similar to conferencing that allows three people to talk at the same time, except in monitoring, one person only listens or typically records. As a result, governments have legally mandated telephone service providers to provide public services with the ability to centrally monitor calls. In democratic countries, the interception of information is carried out on the basis of special rules (for example, the decision of a judge or prosecutor) and control procedures (for example, the Communications Privacy Authority – ΑΔΑΕ).

Like any backdoor, this centralized interception is by no means harmless. We saw this in Greece in 2004, when US intelligence agents were later found to have illegally activated a mobile operator’s interception system to intercept messages from dozens of government officials and politicians.

Things changed again when technology visionary and Apple co-founder Steve Jobs introduced the first iPhone in 2007. Unlike most mobile phones of the time, the iPhone could easily run applications made by other companies, just as it had been done on personal computers up until that time. This has created a new problem for law enforcement since communication through these applications (eg Gmail, Messenger, Snapchat, Viber, WhatsApp) is encrypted and therefore cannot be included in their lawful interception systems by telecom operators. Therefore, in order for, for example, the police to be able to read the messages of members of a criminal organization, they will have to separately apply with a court decision to each application developer that transmits and processes these messages. Since millions of different applications can run on modern mobile phones, this process is extremely complex and time consuming.

Some mobile phone applications are designed in such a way that even the company that runs them does not have access to their users’ communications. This creates an additional headache for government agencies that want to control communications. While there are legal provisions that, under certain conditions, oblige companies to provide agencies with the data they request, there is (yet) no legal framework obliging companies to build their applications in such a way that the state can spy on their users. This happened in 2016 in the United States, when the FBI was unable to force Apple to give him access to the data of a terrorist device (however, this did not prevent others, also government agencies, from hacking these devices).

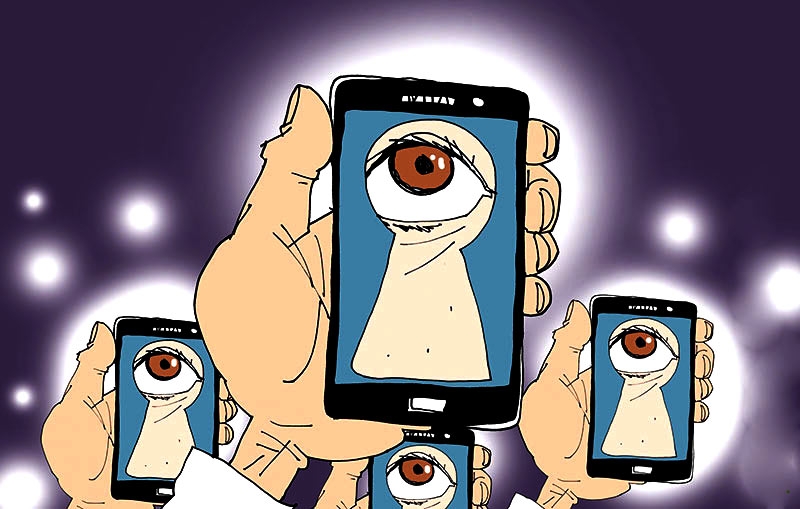

The solution to the problem of “hard-of-hearing” government bodies has become private companies that create and sell high-tech and, of course, expensive surveillance systems for mobile phones. These companies discover vulnerabilities in certain types of phones (the equivalent of a window in a skyscraper that doesn’t close well) and use them to take full control of the device, ie. you can, for example, hear what is being said, see the screen, find out what they are writing, and find out where the device is at any given time. One such system is Predator, which appears to have targeted Greek users’ mobile phones through fake websites.

The use of the Predator system in Greece highlights three major issues:

Firstly, the need to create a regulatory framework for such systems. Companies that have such systems, and the governments that implement them, should be required by law to offer and operate a monitoring and reporting infrastructure equivalent to existing call interception systems. This infrastructure will allow interception only if legal license data is entered, and all interception activities will be logged so that they can be verified by competent authorities such as ΑΔΑΕ.

Secondly, use of legislative repeal of message confidentiality by government agencies. According to the authority’s activity report, ΑΔΑΕ received 3,190 declassification orders from judicial council communications in 2020, compared to 13,751 orders related to national security concerns. Although ΑΔΑΕ avoids commenting on these two figures, the difference seems disproportionate, and national security interception orders are significantly higher than in other democracies. Therefore, perhaps the system of checks and balances that exists in Greece regarding the abolition of secrecy on national security grounds should be strengthened.

Thirdly, how the European Union treats Predator-type systems. I have already spoken about the need for their regulation. Should they be banned altogether? This would greatly increase the security of communications for all citizens, but would make it more difficult for government services that rely on them. Instead of these systems being developed in the “wild west”, should mobile device manufacturers be required to add legal surveillance capability to them? However, our life in such an institutionalized Panopticon seems to be a nightmare, and at the same time, this monitoring capability is sure to become an excellent target for cyberattacks and a tool for authoritarian regimes. Unfortunately, there is no simple and obvious answer to the last problem.

*Diomidis Spinellis is Professor in the Department of Management Science and Technology at the Athens University of Economics and Business and in the Department of Software Engineering at the Delft University of Technology.

More Stories

4 scenarios for the development of the war in Ukraine

There was a scandal in Cyprus over the Prime Minister's plane, donated by K. Mitsotakis

Nuclear wrestling between the USA and Russia: are we heading towards the use of strategic weapons?